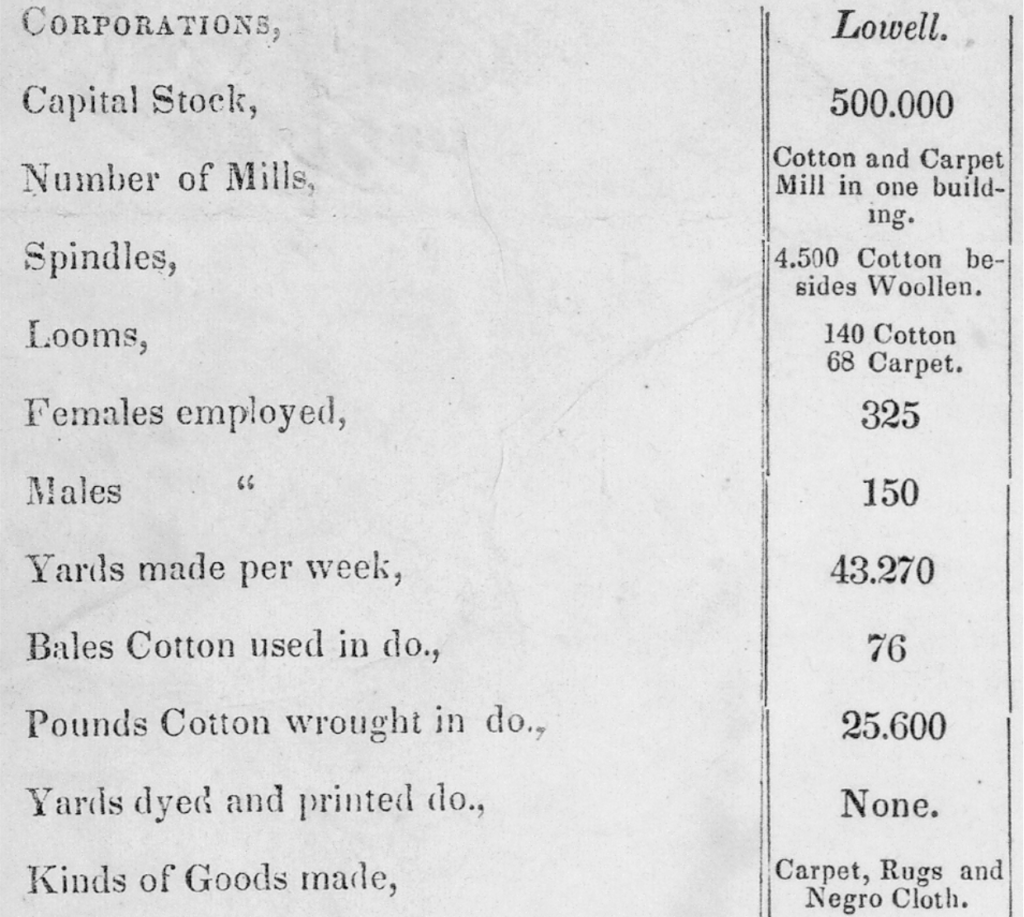

Lowell factories could not function without the enslaved labor in the South. The Lowell Manufacturing Company in the early 1800s (now Market Mills) made coarse, heavy cloth specifically to sell back to slave owners, called “negro cloth.” The factories profited greatly from this. Some formerly enslaved people referred to the same material as “Lowell cloth” in interviews conducted by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s. A formerly enslaved person, Mariah Synder, said “We wore lowell clothes and I never seed no other kind of dress till after surrender.”

More of the Story

Most Lowell factories relied on enslaved labor for raw materials. However, the Lowell Manufacturing Company (now the Market Mills) actually made cloth specifically to sell back to slave owners. This cheap fabric, known as “negro cloth,” was uncomfortable and tore easily. In interviews with formerly enslaved people, some called this fabric “Lowell cloth.”

The Lowell Company made great profits selling this inexpensive fabric to enslavers. For plantation owners, purchasing this material further strengthened relationships with Northern businessmen. To keep the cost of cotton low, many investors in Lowell also contributed to pro-slavery causes and fought against abolitionists in the city. At the center of this economic web were the enslaved people who wore the “Lowell cloth” to pick cotton for the textile industry.

Surprisingly, one of the superintendents of this company was an anti-slavery activist. A devout Quaker, Royal Southwick (1795-1875) joined the Lowell Company in 1829 to supervise carding and spinning, securing significant profits for the company and himself. Yet he and his wife Direxa also helped establish the city’s Anti-Slavery societies. The Southwicks even invited anti-slavery speakers like Frederick Douglass and Britain’s George Thompson into their Tyler Street home. Active in the Whig party, Southwick chaired the city’s Whig committee and served in the state Senate where he petitioned for abolition. Eventually he resigned from the Lowell Company, and invested in a North Chelmsford mill which used wool, not cotton.

To read references to “Lowell Cloth” taken from 39 different interviews with formerly enslaved people conducted by the Works Progress Administration [WPA] in the 1930s, check out the UML Library website. For more information on that project, check out the Library of Congress page about it.

(Thanks Lowell National Historical Park)