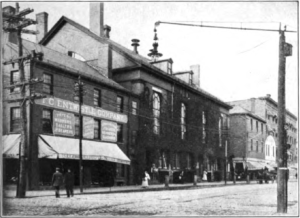

Nathaniel Booth, barbershop owner and freedom seeker, opened a barbershop in 1844 in this building, then called Mechanic’s Hall. It was a hub of abolitionist activity. In 1850, rumors circulated that “manstealers” were coming to kidnap people who had liberated themselves from slavery, and many, including Booth, fled to Canada. Booth came back a year later, then enslavers plotted to strip away his freedom. Nathaniel Booth was able to retain his freedom because Linus Child, a Boott Mill manager, fundraised to pay for it.

The term ‘freedom seeker’ illustrates the African American decision to wrest control of his or her status from the slaveholder to one of their own choosing

‘Manstealers’ was a common term used for those sent to seek and capture freedom seekers

More of the Story

Mechanic’s Hall was built in 1835 by the Middlesex Mechanics Association as a meeting place and library for skilled craftsmen. In addition to hosting meetings, lectures, and fundraising efforts, a portion of the building was set aside for businesses.

In 1844, Nathaniel Booth (1825-1901) opened a barbershop on the first floor of Mechanic’s Hall. Booth was a fugitive from the state of Virginia. Together with Edwin Moore (another fugitive from slavery) Booth worked in Mechanics Hall when it was a hub of abolitionist activity. For these and other Black men living in Northern cities, owning a barber shop was one way to find stability and independence.

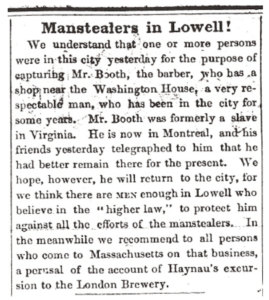

In 1850, rumors circulated that “manstealers” were coming to Lowell to kidnap people who had liberated themselves from slavery. Booth, Moore, and more than twenty others fled to Canada, though Booth did return to Lowell within a year. In 1851, slave catchers demanded Booth’s return to his former owner. Linus Child, an agent for the Boott Cotton Mills, negotiated the price of freedom, then fundraised within the community to ensure that Booth could reestablish his place in Lowell.

As a free man, Booth began to travel the northeast, giving speeches advocating for abolition. In his travels, he met Fanny LeCount Johnson in Philadelphia, who he married in 1858. He returned to Lowell and later Boston during the Civil War and died in Philadelphia in 1901.

(Thanks Lowell National Historical Park)